Abstract

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is based on the following findings: (1) acute attacks of abdominal pain and tenderness in the epigastric region, (2) elevated blood levels of pancreatic enzymes, and (3) abnormal diagnostic imaging findings in the pancreas associated with acute pancreatitis. In Japan, in accordance with criteria established by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, the severity of acute pancreatitis is assessed based on the clinical signs, hematological findings, and imaging findings, including abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Severity must be re-evaluated, especially in the period 24 to 48 h after the onset of acute pancreatitis, because even cases diagnosed as mild or moderate in the early stage may rapidly progress to severe. Management is selected according to the severity of acute pancreatitis, but it is imperative that an adequate infusion volume, vital-sign monitoring, and pain relief be instituted immediately after diagnosis in every patient. Patients with severe cases are treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, a continuous high-dose protease inhibitor, and continuous intraarterial infusion of protease inhibitors and antimicrobial agents; continuous hemodiafiltration may also be used to manage patients with severe cases. Whenever possible, transjejunal enteral nutrition should be administered, even in patients with severe cases, because it seems to decrease morbidity. Necrosectomy is performed when necrotizing pancreatitis is complicated by infection. In this case, continuous closed lavage or open drainage (planned necrosectomy) should be the selected procedure. Pancreatic abscesses are treated by surgical or percutaneous drainage. Emergency endoscopic procedures are given priority over other methods of management in patients with acute gallstone-associated pancreatitis, patients suspected of having bile duct obstruction, and patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis complicated by cholangitis. These strategies for the management of acute pancreatitis are shown in the algorithm in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical questions

-

CQ1.

How is acute pancreatitis diagnosed?

-

CQ2.

What is the basic initial management of acute pancreatitis?

-

CQ3.

Is an evaluation of the etiology of acute pancreatitis necessary in the initial management?

-

CQ4.

Why is a severity assessment of acute pancreatitis necessary in the initial management?

-

CQ5.

When should patients with acute pancreatitis be transferred to a specialist hospital?

-

CQ6.

Why are contrast-enhanced CT scanning and MRI used in the management of acute pancreatitis?

-

CQ7.

What is important in the critical care of severe acute pancreatitis?

-

CQ8.

What are some optional therapies for severe acute pancreatitis?

-

CQ9.

How can the complications of acute pancreatitis be assessed?

-

CQ10.

Is the endoscopic approach beneficial in the treatment of acute gallstone-induced pancreatitis?

-

CQ11.

Is one-stage cholecystectomy followed by common bile duct (CBD) clearance safer and more effective than endoscopic procedures?

-

CQ12.

When should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be undertaken in patients with gallstone pancreatitis?

Basic medical treatment policy (see flowchart in Fig. 1)

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for acute pancreatitis were created a few years ago,1 but several modifications have been made, thanks to consensus conferences and a great deal of feedback. The flowchart in Fig. 1 illustrates the details of the current Guidelines according to the procedures and the timing of their performance. A brief explanation of each point is provided in this article, but please refer to the corresponding text in the Guidelines for details.2–9

Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis5

Clinical question (CQ) 1. How is acute pancreatitis diagnosed?

Acute pancreatitis is diagnosed based on a comprehensive assessment of the clinical manifestations, including elevated extrapancreatic enzyme levels and imaging findings in the pancreas (Recommendation A).

In 1990, the Research Group for Intractable Diseases and Refractory Pancreatic Diseases, which was sponsored by the then Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, established the criteria for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in Japan (Table 1), and these criteria have been used as the gold standard ever since. Acute pancreatitis must be differentiated from other conditions. Acute abdomen, gastrointestinal perforation, acute cholecystitis, ileus, mesenteric artery occlusion, and acute aortic dissection must all be ruled out.

Basic management7

CQ2. What is the basic initial management of acute pancreatitis?

Adequate fluid infusion (Recommendation A), vitalsign monitoring, and respiratory and cardiovascular management should be performed in the early stage, immediately after diagnosis is made. Research done in Japan in 2004 reported the infusion volume on the first day in hospital to be less than 3500 ml in 41 (61.2%) of 67 patients who later died. An adequate infusion volume should be given in the early stage, because some cases diagnosed initially as mild can rapidly progress to severe.

Pain relief with analgesics is necessary in patients with acute pancreatitis with associated pain, because the pain may cause mental distress and adversely impact the course of treatment by, for example, causing tachypnea. Gastric suction with a nasogastric tube (Recommendation D) is unnecessary in mild or moderate cases, unless acute pancreatitis is associated with paralytic ileus or frequent nausea/vomiting. H2 blockers are also unnecessary unless a stress ulcer develops (Recommendation D).

Identification of etiological factors in acute pancreatitis5

CQ3. Is an evaluation of the etiology of acute pancreatitis necessary in initial management?

Etiological factors in acute pancreatitis should be identified promptly and accurately, because, together with the severity assessment, they have a major impact on the treatment policy. It is particularly important to differentiate acute gallstone-associated pancreatitis from acute alcoholic pancreatitis, because the two manifestations require different management procedures, with the former including management of the bile duct system (Recommendation A)

Because different types of acute pancreatitis have different treatments, each patient should be evaluated immediately for the presence of the following abnormal findings related to etiology: leaking hepatic enzymes (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) and biliary system enzymes (alkaline phosphatase [ALP], lactate dehydrogerase [LDH], and guanosine triphosphate [GTP]), investigated using blood biochemistry studies; and cholecystocholedocholithiasis and cholangiectasis, investigated using ultrasonography (US) examination. Biliary sand and fine gallbladder stones may be found later, even in patients in whom cholecystocholedocholithiasis is not detectable in the acute stage. Therefore, patients should be repeatedly examined for cholecystocholedocholithiasis, even after the acute stage.

Assessment of the severity of acute pancreatitis6

CQ4. Why is a severity assessment of acute pancreatitis necessary in the initial management?

Severity assessment ensures appropriate management (Recommendation A). Because mild acute pancreatitis in the early stage may rapidly progress to severe pancreatitis, continuous evaluation is necessary, particularly within the first 3 days of onset

Severity assessment according to severity scoring systems (JPN score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation [APACHE] II score) is important in deciding treatment policy and judging whether transfer to a specialist unit is necessary (Recommendation A). Severity assessment on the basis of the JPN score is recommended in Japan.

Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis should be followed by a severity assessment and a management strategy appropriate to the level of severity. The Japanese criteria and scoring system allow sequential scoring and are useful for deciding on treatment policy. Use of this system has improved the survival rate.

Because even mild to moderate cases may progress to severe during the early stage, particularly within 72 h of onset, severity should be re-evaluated within 24 to 48 h of onset and again within 48 to 72 h of onset.

The outcome for patients whose acute pancreatitis progressed from mild or moderate to severe was found to be poor in a Japanese study done in 2004.

Transfer to advanced specialist medical institutions6

CQ5. When should patients with acute pancreatitis be transferred to a specialist hospital?

A JNP score of 2 or more is the criterion for transfer (Recommendation A). It is desirable to transfer patients with severe acute pancreatitis to a medical institution where monitoring and systemic management are available

In principle, acute pancreatitis should be treated on an inpatient basis. The criteria for evaluating the severity of acute pancreatitis established by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare6 (JMHLW Criteria) have been used widely in Japan to assess the severity of acute pancreatitis. It is desirable to transfer patients diagnosed with severe pancreatitis, based on these criteria, to a medical institution with fulltime surgeons and physicians specializing in gastroenterology. In view of their significantly higher mortality rate, it has been reported (Level 3b) [89] that patients with a severity score of 8 or more according to the JMHLW Criteria or an APACHE II score of 13 or more within the first 24 to 48 h after onset should be transferred, preferably to an institution where they can be cared for by fulltime physicians who specialize in intensive care, endoscopic treatment, radiological intervention, and cholangiopancreatic surgery. Patients with cases diagnosed as moderate also need to receive an adequate volume of fluid infusion, meticulous monitoring of their clinical course, and assessment of indications for transfer to advanced medical institutions, because their acute pancreatitis may progress to severe pancreatitis. The decision to transfer a patient should be made carefully, taking into consideration the potential impact of a long trip on the patient’s condition.

It is desirable to transfer a patient with severe acute pancreatitis (JMHLW criteria severity score of 2 or more) to a medical institution where monitoring and systemic management are available and where the patient will receive an adequate medical examination.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT)5,7

CQ6. Why are contrast-enhanced CT scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) used in the management of acute pancreatitis?

Contrast-enhanced CT scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential for severity assessment and for making decisions about management policy (Recommendation A).

The presence and extent of pancreatic necrosis and the extent of inflammatory change are correlated with severity. Contrast-enhanced CT or contrast-enhanced MRI is required to make a definite judgment regarding the presence and extent of pancreatic necrosis. However, it should be noted that contrast media may cause adverse reactions.

The presence of pancreatic necrosis and the extent of inflammatory change are closely correlated with various complications and the mortality rate (Levels 1b–3b) [57–59] and may influence the selection of management methods, including the administration of prophylactic antimicrobial agents and intraarterial infusion therapy. Inflammatory change in the peripancreatic tissue can be evaluated by plain CT, but, because it is usually difficult to diagnose pancreatic necrosis, contrast-enhanced CT scanning (Level 1c) [60] is required to identify and determine the extent of pancreatic necrosis. However, while one study has shown that the use of contrast medium does not exacerbate the pathological conditions of pancreatitis (Level 2b) [61], another has shown that its use exacerbates pancreatitis (Level 2b) [62] and that the use of contrast medium may also exacerbate nephropathy, thereby complicating severe acute pancreatitis. In view of the above findings, contrast-enhanced CT should be performed only when the value of the information to be obtained exceeds disadvantages such as impairment of renal function or an allergic reaction. The possible advantages of contrast-enhanced CT are the visualization of pancreatic necrosis, the usefulness of the findings in assessing the need for surgical management and drainage, and occasional visualization of false aneurysms, which may provide an opportunity to prevent their rupture.

Intensive care7

CQ7. What is important in the critical care of severe acute pancreatitis?

Appropriate infusion management, strict cardiovascular and respiratory management, and the prevention and management of organ failure and infection are all important

Acute pancreatitis requires the basic management strategies that are described above. In critical cases, oxygen administration, artificial respiration (ventilation), and management of electrolytes and blood sugar should be performed as required.

Continuous intravenous infusion of massive doses of protease inhibitors may decrease the incidence of complications in severe acute pancreatitis (Recommendation B).

Because transjejunal enteral nutrition is superior to total parenteral nutrition in the nutritional management of pancreatitis, enteral nutrition should be administered unless there are manifestations of ileus (Recommendation A).

The prophylactic use of antimicrobial agents is unnecessary in mild and moderate cases, but the administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents with good penetration into pancreatic tissue is required in severe cases, as this will help prevent infection (Recommendation A).

Optional procedures for severe cases7

CQ8. What are some optional therapies for severe acute pancreatitis?

Blood purification therapy is used in the management of severe acute pancreatitis, and continuous regional pancreatic-arterial infusion of protease inhibitors/antimicrobial agents is used in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis (Recommendation C)

Selective digestive decontamination (SDD) can be used in severe cases, but, because there has been only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of SDD (with a limited number of patients), it remains unclear whether systemic administration of antimicrobiotics or the combined use of the systemic administration of antimicrobiotics and SDD is more efficacious (Recommendation C).

Blood purification, particularly continuous hemodiafiltration (CHDF), may prevent severe acute pancreatitis from progressing to multiple organ failure (Recommendation C). Continuous regional pancreaticarterial infusion of protease inhibitors/antimicrobial agents may decrease the mortality rate and the incidence of infectious complications in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis (Recommendation C). However, the efficacy of blood purification and pancreatic-arterial infusion therapy will remain uncertain until confirmed by a high quality RCT. An RCT of continuous pancreatic-arterial infusion is currently underway.

Assessing the complications of acute pancreatitis8

CQ9. How can the complications of acute pancreatitis be assessed?

Patients should be examined for complications of acute pancreatitis, i.e., infected pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess, by abdominal ultrasonography (US) and abdominal CT scanning (Recommendation A)

Other recommendations are as follows:

-

(1)

CT- or US-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) should be performed when infected pancreatic necrosis is suspected (Recommendation A).

-

(2)

Infected pancreatic necrosis with signs of sepsis is an indication for surgical intervention (Recommendation B).

-

(3)

Noninfected pancreatic necrosis is usually managed conservatively, in general, but those cases in which the patient’s condition does not improve (or visceral disorders progress and infection cannot be ruled out) are candidates for surgical intervention (Recommendation B).

-

(4)

Early surgery is not recommended for necrotizing pancreatitis in the absence of specific indications (Recommendation B).

-

(5)

Necrosectomy is recommended for the surgical management of infected pancreatic necrosis (Recommendation A).

-

(6)

Simple drainage should be avoided as a method of post-necrosectomy management, and continuous closed lavage or open drainage (planned necrosectomy) should be selected instead (Recommendation B).

-

(7)

Pancreatic abscess should be managed by surgical or percutaneous drainage (Recommendation C).

-

(8)

Pancreatic abscesses that do not respond clinically to percutaneous drainage should be immediately treated by surgical drainage (Recommendation B).

-

(9)

Symptomatic cases, acute pancreatitis cases with complications, and pancreatic pseudocysts whose diameter is increasing should be treated by drainage (Recommendation A).

-

(10)

Surgical intervention should be selected for those pancreatic pseudocysts that do not tend toward improvement in response to percutaneous or endoscopic drainage (Recommendation A).

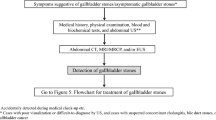

Management policy for gallstone pancreatitis (Fig. 2)9

CQ10. Is the endoscopic approach beneficial in the treatment of acute gallstone-induced pancreatitis?

Emergency endoscopic procedures should be given priority in patients with acute gallstone-associated pancreatitis with suspected bile duct obstruction and in cases complicated by cholangitis (Recommendation A)

When a diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis is made (based on imaging and blood biochemistry findings performed immediately after medical examination), the patient should be examined for cholangitis and transit disorders in the biliary tract, and severity should be assessed. If the above complications are present, emergency endoscopic procedures (biliary calculus removal and common bile duct drainage) are used, in combination with the management of severe pancreatitis.

When these procedures cannot be used, percutaneous biliary duct drainage or surgical decompression is performed, as needed. Whether these drainage procedures are selected depends on the patient’s condition and the availability of specialist medical professionals and the appropriate institution.

Emergency endoscopic procedures (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography [ERC] ± endoscopic sphincterotomy [ES], endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation [EPBD], endoscopic nasobiliary drainage [ENBD], and stenting) are designed to remove biliary calculi and to drain the biliary tract, and they can often relieve any occlusion of the pancreatic duct.

It is important to transfer patients to an advanced specialist medical institution if they are not able to undergo the needed procedures at the institution where they are being treated.

CQ11. Is one-stage cholecystectomy followed by common bile duct (CBD) clearance safer and more effective than endoscopic procedures?

Open choledochotomy or sphincterotomy (surgical removal of CBD stones) is recommended (Recommendation D)

An RCT (Level 1b) [45] that compared patients who had early surgery (within 72 h after hospitalization) and those who had delayed surgery found that there was no difference in the incidence of complications (8.3% vs 10.3%) or mortality (2.8% vs 6.9%) between the early group and the delayed group. Another RCT (Level 1b) [46] revealed that early surgery (within 48 h of hospital admission) was followed by a significantly higher incidence of complications (30.1% vs 5.1%) and mortality (15.1% vs 2.4%) than was delayed surgery (from 48h onward after hospital admission). Because endoscopic procedures such as ERC+ES can now be performed safely, surgical removal or drainage of gallstones in the acute stage is not recommended if these endoscopic procedures are indicated.

CQ12. When should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be undertaken in patients with gallstone pancreatitis?

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same hospital stay as the initial treatment is recommended for patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis without complications (Recommendation B). Choledochotomy and/or choledocholithotomy are performed when deemed necessary

In recent years laparoscopic operations have been increasingly used to treat many patients with gallstone-induced pancreatitis. According to the results of prospective cohort studies (Levels 1b–2c) [16–21], the percentage of patients in whom laparoscopic cholecystectomy was completed was 94.5% (range, 79% to 100%), the incidence of complications was 5.5% (range, 0% to 10%), and the mortality rate was 0.4% (range, 0% to 2.5%), suggesting that the outcome of laparoscopic operations is equal to or better than that of laparotomy. Based on the above data, laparoscopic cholecystectomy may also be used in the management of mild gallstone pancreatitis.

References

T Mayumi H Ura S Arata N Kitamura I Kiriyama K Shibuya et al. (2002) ArticleTitleEvidence-based clinical practice guidelines for acute pancreatitis: proposals J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 9 413–22 10.1007/s005340200051 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s005340200051 Occurrence Handle12483262

T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida M Sekimoto et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: cutting-edge information J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 2–6 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1045-5 Occurrence Handle16463205

M Yoshida T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Sekimoto et al. (2006) ArticleTitleHealth insurance system and payments provided to patients for management of severe acute pancreatitis in Japan J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 7–9 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1046-4 Occurrence Handle16463206

M Sekimoto T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: epidemiology, etiology, natural history, and outcome predictors in acute pancreatitis J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 10–24 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1047-3 Occurrence Handle16463207

M Koizumi T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 25–32 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1048-2 Occurrence Handle16463208

M Hirota T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: severity assessment of acute pancreatitis J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 33–41 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1049-1 Occurrence Handle16463209

K Takeda T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: medical management of acute pancreatitis J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 42–47 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1050-8 Occurrence Handle16463210

S Isaji T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: surgical management J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 48–55 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1051-7 Occurrence Handle16463211

Y Kimura T Takada Y Kawarada K Hirata T Mayumi M Yoshida et al. (2006) ArticleTitleJPN guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: treatment of gallstone-induced acute pancreatitis J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13 56–60 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00534-005-1052-6 Occurrence Handle16463212

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

About this article

Cite this article

Mayumi, T., Takada, T., Kawarada, Y. et al. Management strategy for acute pancreatitis in the JPN Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 13, 61–67 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-005-1053-5

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-005-1053-5